Correlations of plasma cyclin-dependent kinase 9 level with disease progression and prognosis in patients with acute large artery atherosclerotic cerebral infarction

-

摘要:目的

探讨大动脉粥样硬化(LAA)型脑梗死患者病情进展及预后的影响因素,并分析血浆细胞周期依赖性激酶9 (CDK9)水平在LAA型脑梗死诊治中的价值。

方法选择2022年3月1日—2023年11月20日在扬州大学附属医院神经内科住院的急性脑梗死患者为研究对象。根据诊断标准,选择急性LAA型脑梗死患者98例为LAA组,急性小动脉闭塞性脑梗死(SAO)患者33例为SAO组; 同时,纳入健康体检中心的年龄、性别匹配的健康体检者40例为对照组。按照LAA型脑梗死患者病情是否进展分为进展型脑梗死(PCI)组(39例)及非进展型脑梗死(NPCI)组(59例)。98例LAA型脑梗死患者在3个月随访过程中失访6例,根据随访90 d时改良Rankin量表(mRS)评分将其分为预后良好(mRS评分≤2分, 59例)组和预后不良(mRS评分>2分, 33例)组。收集研究对象入院后第2天空腹血脂指标[总胆固醇(TC)、甘油三酯(TG)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(HDL-C)、血糖(GLU)、糖化血红蛋白(HbA1c)、同型半胱氨酸(Hcy)]。脑梗死患者神经功能缺损程度采用美国国立卫生研究院卒中量表(NIHSS)评分进行评估。采用酶联免疫吸附测定法(ELISA)测定不同分组人群血浆CDK9水平; 探讨急性LAA型脑梗死患者病情进展的影响因素; 绘制受试者工作特征曲线评价CDK9对急性LAA的预测价值。

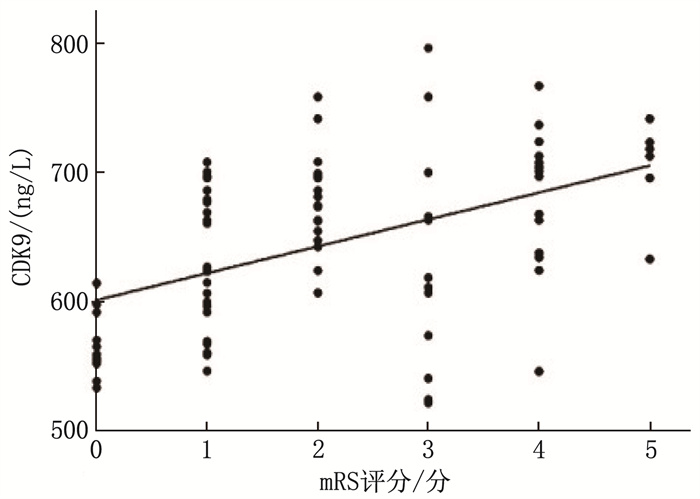

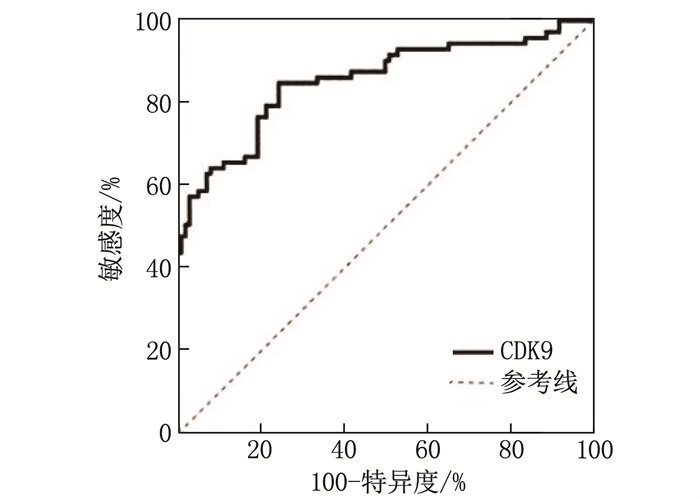

结果与对照组比较, LAA组HDL-C水平更低, CDK9水平更高,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。LAA组较SAO组糖尿病病史占比更高,梗死体积更大,入院时NIHSS评分更高, CDK9水平更高,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。二元Logistic回归分析结果显示,糖尿病病史以及血浆CDK9水平是LAA型脑梗死的影响因素。NPCI组与PCI组糖尿病病史占比、HbA1c、随机GLU和CDK9水平比较,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。有糖尿病病史以及血浆CDK9水平是急性LAA型脑梗死患者病情进展的影响因素。CDK9预测急性LAA型脑梗死的受试者工作特征曲线的曲线下面积为0.854 5(95%CI: 0.794 1~0.914 8), 当CDK9水平为602.1 ng/L时,约登指数最大(0.604), 相应的敏感度为0.849, 特异度为0.755。预后不良组NIHSS评分、梗死体积以及血浆CDK9水平大于或高于预后良好组,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.01)。相关性分析结果显示, mRS评分与CDK9水平呈正相关(r=0.485, P < 0.01)。

结论急性LAA型脑梗死患者血浆CDK9水平显著升高, CDK9是急性LAA型脑梗死的影响因素。血浆CDK9水平与急性脑梗死病情进展和预后不良呈正相关,对LAA型脑梗死的进展有一定预测价值。

-

关键词:

- 急性大动脉粥样硬化型脑梗死 /

- 细胞周期依赖性激酶9 /

- 美国国立卫生研究院卒中量表 /

- 进展性脑卒中 /

- 预后

Abstract:ObjectiveTo investigate the influencing factors of disease progression and prognosis in patients with large artery atherosclerotic (LAA) cerebral infarction and analyze the value of plasma cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) level in the diagnosis and treatment of LAA cerebral infarction.

MethodsPatients with acute cerebral infarction admitted to the Department of Neurology of the Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University between March 1, 2022, and November 20, 2023, were selected. According to the diagnostic criteria, 98 patients with acute LAA (LAA group) and 33 patients with acute small artery occlusion (SAO) cerebral infarction (SAO group) were selected. Additionally, 40 healthy individuals matched for age and gender from the Health Examination Center were included as control group. Based on whether the condition of LAA cerebral infarction patients progressing, they were divided into progressive cerebral infarction (PCI) group (39 patients) and the non-progressive cerebral infarction (NPCI) group (59 patients). During the 3-month follow-up period, 6 patients from the 98 LAA cerebral infarction patients were lost. According to the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days of follow-up, patients were divided into good prognosis group (mRS score ≤ 2, 59 patients) and poor prognosis group (mRS score >2, 33 patients). Fasting lipid indices [total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), glucose (GLU), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and homocysteine (Hcy)] were collected on the second day after admission. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was used to assess the degree of neurological impairment in cerebral infarction patients. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to measure plasma CDK9 levels in different groups; factors influencing disease progression in patients with acute LAA cerebral infarction were explored; and receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted to evaluate the predictive value of CDK9 in patients with acute LAA cerebral infarction.

ResultsCompared with the control group, the LAA group had lower HDL-C level and higher CDK9 level (P < 0.05). The LAA group had a higher proportion of diabetes history, larger infarction volume, higher NIHSS score at admission, and higher CDK9 level compared with the SAO group (P < 0.05). Binary Logistic regression analysis showed that diabetes history and plasma CDK9 levels were influencing factors for LAA cerebral infarction. There were statistically significant differences in the proportion of diabetes history, HbA1c, random GLU, and CDK9 levels between the NPCI and PCI groups (P < 0.05).Diabetes history and plasma CDK9 levels were influencing factors for disease progression in patients with acute LAA cerebral infarction. The area under the ROC curve for CDK9 in predicting acute LAA cerebral infarction was 0.854 5 (95%CI, 0.794 1 to 0.914 8). When the CDK9 level was 602.1 ng/L, the Youden index was maximum (0.604), with a corresponding sensitivity of 0.849 and specificity of 0.755.The NIHSS score, infarction volume, and plasma CDK9 level were higher in the poor prognosis group compared with the good prognosis group (P < 0.01). Correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between mRS scores and CDK9 levels (r=0.485, P < 0.01).

ConclusionPlasma CDK9 levels are significantly elevated, and is an influencing factor. It is positively correlated with disease progression and poor prognosis in acute cerebral infarction and has certain predictive value for the progression of LAA cerebral infarction.

-

-

表 1 LAA组与对照组基线资料比较(x±s)[n(%)][M(Q1, Q3)]

基线资料 LAA组(n=98) 对照组(n=40) 年龄/岁 67.89±13.54 64.08±9.74 男 62(63.33) 23(57.50) 高血压 81(82.65)* 34(85.00) 糖尿病 48(48.98) 17(42.50) 吸烟 30(30.61) 15(37.50) TC/(mmol/L) 4.51±1.08 5.20±0.71 TG/(mmol/L) 1.66(1.34, 2.39) 1.79(1.24, 2.24) LDL-C/(mmol/L) 2.58±0.38 2.65±0.71 HDL-C/(mmol/L) 1.18±0.21* 1.36±0.33 Hcy/(μmol/L) 10.47±3.85 10.65±2.75 CDK9/(ng/L) 646.01±63.40* 518.85±66.73 LAA: 大动脉粥样硬化; TC: 总胆固醇; TG: 甘油三酯;

LDL-C: 低密度脂蛋白胆固醇; HDL-C: 高密度脂蛋白胆固醇;

Hcy: 同型半胱氨酸; CDK9: 周期蛋白依赖性激酶9。

与对照组比较, * P < 0.05。表 2 LAA组与SAO组患者基线资料比较(x±s)[n(%)][M(Q1, Q3)]

基线资料 LAA组(n=98) SAO组(n=33) t/Z/χ2 P 年龄/岁 67.89±13.54 66.42±9.37 0.57 0.57 男 62(63.33) 21(63.64) 0.01 0.97 BMI/(kg/m2) 25.15±3.06 24.01±2.40 1.95 0.05 高血压 81(82.65) 25(75.76) 0.76 0.38 糖尿病 48(48.98) 9(27.28) 4.73 < 0.05 吸烟史 30(30.61) 15(45.46) 2.35 0.12 冠心病 20(20.41) 2(6.06) 3.63 0.06 入院时间 ≤24 h 58(59.18) 19(57.58) 1.80 0.41 >24~48 h 26(26.53) 7(21.21) >48 h 14(14.29) 7(21.21) 梗死体积 ≤5 cm3 46(46.94) 22(66.67) 6.10 < 0.05 >5~10 cm3 23(23.47) 8(24.24) >10 cm3 29(29.59) 3(9.09) NIHSS评分/分 4.00(2.00, 7.25) 2.00(1.00, 4.00) -3.39 < 0.05 HbA1c/% 6.35(5.57, 8.20) 6.00(5.60, 7.10) -0.98 0.32 随机GLU/(mmol/L) 6.78(5.45, 8.21) 6.35(5.56, 7.91) -0.64 0.52 Hcy/(μmol/L) 10.47±3.85 11.25±4.33 -0.97 0.33 TC/(mmol/L) 4.51±1.08 4.42±0.92 0.45 0.65 TG/(mmol/L) 1.66(1.34, 2.39) 1.64(1.18, 2.77) -0.46 0.64 LDL-C/(mmol/L) 2.58±0.38 2.66±0.76 0.16 0.87 HDL-C/(mmol/L) 1.18±0.21 1.15±0.25 0.68 0.49 CDK9/(ng/L) 646.01±63.40 549.26±90.92 5.56 < 0.01 BMI: 体质量指数; NIHSS: 美国国立卫生研究院卒中量表; HbA1c: 糖化血红蛋白; GLU: 血糖; Hcy: 同型半胱氨酸。 表 3 影响LAA型脑梗死发生的二元Logistic回归分析

变量 β SE Wald χ2 P OR 95%CI 年龄 0.038 0.024 2.394 0.122 1.038 0.990~1.089 性别 1.174 0.671 3.061 0.080 3.234 0.868~12.043 高血压 0.945 0.645 2.149 0.143 2.573 0.727~9.102 糖尿病 1.514 0.606 6.240 0.012 4.545 1.386~14.911 吸烟史 -0.480 0.609 0.622 0.430 0.619 0.187~2.041 TC 0.279 0.319 0.764 0.382 1.322 0.707~2.470 LDL-C 0.043 0.496 0.007 0.931 1.044 0.395~2.762 TG -0.519 0.279 3.475 0.062 0.595 0.345~1.027 Hcy -0.078 0.060 1.692 0.193 0.925 0.823~1.076 CDK9 0.019 0.004 19.533 < 0.001 1.019 1.010~1.027 常量 -13.831 3.863 12.822 < 0.001 < 0.001 — 表 4 PCI组与NPCI组患者基线资料比较(x±s)[n(%)][M(Q1, Q3)]

基线资料 PCI组(n=39) NPCI组(n=59) t/Z/χ2 P 年龄/岁 65.79±12.87 69.15±13.77 -1.250 0.214 男 24(61.54) 39(66.10) 0.083 0.773 BMI/(kg/m2) 25.62±2.67 24.88±4.26 1.233 0.221 高血压 29(74.36) 25(42.37) 3.108 0.078 糖尿病 31(79.49) 9(15.25) 24.127 < 0.001 吸烟史 9(23.08) 15(25.42) 1.732 0.188 冠心病 10(25.6%) 2(3.39) 1.092 0.296 NIHSS评分/分 5.0(1.00, 9.00) 4.0(2.00, 7.00) -0.668 0.504 梗死体积 ≤5 cm3 19(48.72) 28(47.46) 1.191 0.551 >5~10 cm3 7(17.95) 15(25.42) >10 cm3 13(33.33) 16(27.12) HbA1c/% 7.40(6.20, 11.2) 5.91(3.91, 4.75) -3.693 < 0.001 肌酸激酶同工酶/(ng/mL) 8.53±4.11 8.87±3.04 -0.723 0.471 随机GLU/(mmol/L) 8.12±2.98 6.78±2.43 2.460 0.016 Hcy/(umol/L) 10.56±4.26 11.02±3.76 0.590 0.557 TC/(mmol/L) 4.41±1.16 4.56±0.92 0.756 0.452 TG/(mmol/L) 1.67(1.32, 2.15) 1.40(1.16, 2.30) -1.002 0.316 LDL-C/(mmol/L) 2.68±0.44 2.68±0.34 -0.019 0.985 HDL-C/(mmol/L) 1.21±0.20 1.16±0.21 1.241 0.218 CDK9/(ng/L) 658.82±65.42 635.26±59.00 2.099 0.038 表 5 血浆CDK9水平与急性LAA型脑梗死病情进展的多因素Logistic回归分析(x±s)

变量 β SE Wald χ2 P OR 95%CI 糖尿病 2.654 0.703 14.258 < 0.001 14.208 3.583~56.333 HbA1c -0.041 0.180 0.530 0.818 0.960 0.675~1.365 随机GLU -0.020 0.110 0.031 0.859 0.981 0.790~1.217 CDK9 0.011 0.004 5.842 0.016 1.011 1.002~1.020 常量 -8.350 2.869 8.472 0.004 < 0.001 — 表 6 预后不良组与预后良好组指标比较(x±s)

指标 预后不良组(n=33) 预后良好组(n=59) P 梗死体积/cm3 9.24±4.99 5.81±4.25 0.001 NIHSS评分/分 7.88±4.66 3.61±2.77 < 0.001 CDK9/(ng/L) 666.63±70.98 633.02±55.53 0.014 -

[1] JING M X, BAO L X Y, SEET R C S. Estimated incidence and mortality of stroke in China[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2023, 6(3): e231468. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1468

[2] TU W J, ZHAO Z P, YIN P, et al. Estimated burden of stroke in China in 2020[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2023, 6(3): e231455. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1455

[3] BJÖRKEGREN J L M, LUSIS A J. Atherosclerosis: recent developments[J]. Cell, 2022, 185(10): 1630-1645. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.004

[4] ADAMS H P Jr, BENDIXEN B H, KAPPELLE L J, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment[J]. Stroke, 1993, 24(1): 35-41. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35

[5] WANG W Z, JIANG B, SUN H X, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults[J]. Circulation, 2017, 135(8): 759-771. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250

[6] 季一飞, 余静梅. 不同TOAST分型急性缺血性脑卒中诊疗指南及专家共识解读[J]. 西部医学, 2022, 34 (11): 1565-1570. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-3511.2022.11.002 [7] SCHMITZ M L, KRACHT M. Cyclin-dependent kinases as coregulators of inflammatory gene expression[J]. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2016, 37(2): 101-113. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.10.004

[8] SUNDAR V, VIMAL S, SAI MITHLESH M S, et al. Transcriptional cyclin-dependent kinases as the mediators of inflammation-a review[J]. Gene, 2021, 769: 145200. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145200

[9] WANG S D, FISCHER P M. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9: a key transcriptional regulator and potential drug target in oncology, virology and cardiology[J]. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2008, 29(6): 302-313. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.03.003

[10] ANSHABO A T, MILNE R, WANG S D, et al. CDK9: a comprehensive review of its biology, and its role as a potential target for anti-cancer agents[J]. Front Oncol, 2021, 11: 678559. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.678559

[11] DONG N, WU X, HONG T, et al. Elevated serum ninjurin-1 is associated with a high risk of large artery atherosclerotic acute ischemic stroke[J]. Transl Stroke Res, 2023, 14(4): 465-471. doi: 10.1007/s12975-022-01077-6

[12] OLIVATO S, NIZZOLI S, CAVAZZUTI M, et al. E-NIHSS: an expanded national institutes of health stroke scale weighted for anterior and posterior circulation strokes[J]. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2016, 25(12): 2953-2957. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.08.011

[13] ZHAO Y, HUA X, REN X W, et al. Increasing burden of stroke in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, incidence, mortality, and case fatality[J]. Int J Stroke, 2023, 18(3): 259-267. doi: 10.1177/17474930221135983

[14] FALK E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2006, 47(8 suppl): C7-12.

[15] KONG P, CUI Z Y, HUANG X F, et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2022, 7(1): 131. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00955-7

[16] HANSSON G K. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 352(16): 1685-1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430

[17] SOEHNLEIN O, LIBBY P. Targeting inflammation in atherosclerosis- from experimental insights to the clinic[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2021, 20(8): 589-610. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00198-1

[18] RAMAN K, CHONG M, AKHTAR-DANESH G G, et al. Genetic markers of inflammation and their role in cardiovascular disease[J]. Can J Cardiol, 2013, 29(1): 67-74. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.06.025

[19] BACON C W, D'ORSO I. CDK9: a signaling hub for transcriptional control[J]. Transcription, 2019, 10(2): 57-75. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2018.1523668

[20] NOE GONZALEZ M, BLEARS D, SVEJSTRUP J Q. Causes and consequences of RNA polymerase Ⅱ stalling during transcript elongation[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021, 22(1): 3-21. http://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/9770a23082e647968ee4c809d143c168ce9ae785

[21] NI W Y, ZHANG F Z, ZHENG L, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) inhibitor atuveciclib suppresses intervertebral disk degeneration via the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020, 8: 579658. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.579658

[22] YANG X J, LUO W, LI L, et al. CDK9 inhibition improves diabetic nephropathy by reducing inflammation in the kidneys[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2021, 416: 115465. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115465

[23] HAN Y M, ZHAO S S, GONG Y Q, et al. Serum cyclin-dependent kinase 9 is a potential biomarker of atherosclerotic inflammation[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(2): 1854-1862. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6443

[24] HAN Y M, ZHAN Y, HOU G H, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 may as a novel target in downregulating the atherosclerosis inflammation (Review)[J]. Biomed Rep, 2014, 2(6): 775-779. doi: 10.3892/br.2014.322

[25] HOODLESS L J, LUCAS C D, DUFFIN R, et al. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of CDK9 drives neutrophil apoptosis to resolve inflammation in zebrafish in vivo[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 5: 36980. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5a58/f86f369a4c666aef041975d49b2b4ed76553.pdf

[26] HUANG S S, LUO W, WU G J, et al. Inhibition of CDK9 attenuates atherosclerosis by inhibiting inflammation and phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells[J]. Aging, 2021, 13(11): 14892-14909. http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34102609/

[27] BANKS J L, MAROTTA C A. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis[J]. Stroke, 2007, 38(3): 1091-1096. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258355.23810.c6

下载:

下载:

苏公网安备 32100302010246号

苏公网安备 32100302010246号